Introduction: The Delicate Balance of Blood

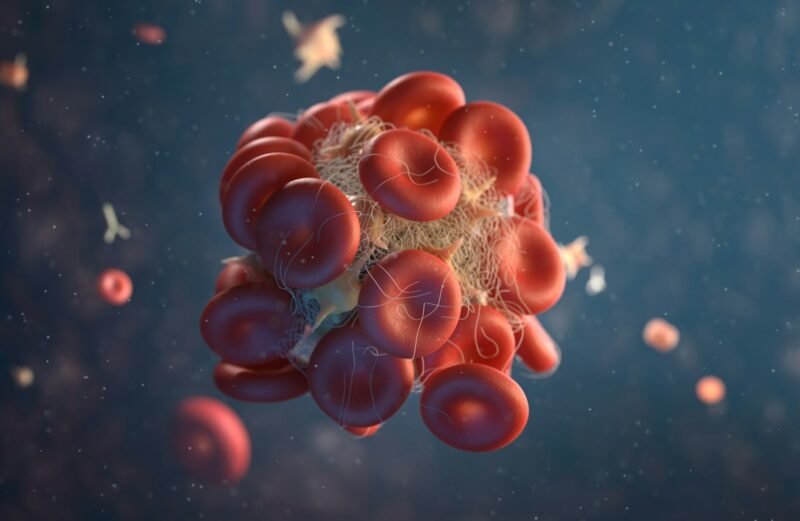

Human blood is a biological marvel. It must remain liquid enough to flow through miles of microscopic capillaries, yet solid enough to clot instantly the moment a vessel is breached. This balance is maintained by a complex domino effect known as the Coagulation Cascade.

When this system fails, the result is either dangerous bleeding (hemorrhage) or dangerous clotting (thrombosis). The Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT) test is the primary tool used to investigate the “Intrinsic Pathway” of this cascade. While often seen as a routine pre-surgical check, the APTT is actually a window into genetic disorders, autoimmune diseases, and the safety of life-saving blood thinners.

The “Cascade” Explained: Why Seconds Matter

Imagine a row of dominoes. When a blood vessel is damaged, a series of proteins (Clotting Factors) activate each other in a specific order: Factor XII activates Factor XI, which activates Factor IX, and so on, finally leading to a Fibrin clot.

The APTT test measures exactly how many seconds this specific sequence takes.

-

Normal Range: Typically 30–40 seconds.

-

Prolonged APTT: If the dominoes fall too slowly (>45 seconds), it means one of the factors is missing, defective, or being blocked.

The “Bleeding” Scenarios: Hemophilia and Von Willebrand A prolonged APTT is the hallmark diagnostic clue for Hemophilia.

-

Hemophilia A (Factor VIII deficiency): The most common severe bleeding disorder.

-

Hemophilia B (Factor IX deficiency): Historically known as “Christmas Disease.”

-

Acquired Hemophilia: A rare but critical condition where the immune system suddenly attacks its own clotting factors later in life. Patients with these conditions may not bleed profusely from a cut finger, but they suffer from internal bleeding into joints (knees, ankles) and muscles, often triggered by minor bumps they don’t even remember.

The “Clotting” Paradox: Lupus Anticoagulant Here is one of the most confusing aspects of hematology: A prolonged APTT can sometimes mean you clot too much. This occurs in Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS), an autoimmune condition. The body produces an antibody (Lupus Anticoagulant) that interferes with the test chemicals in the lab, making the clotting time look long. However, inside the human body, this same antibody actually causes blood to clot inappropriately, leading to recurrent miscarriages or deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

Heparin Monitoring: Walking the Tightrope The most common daily use of APTT is in hospitals for patients taking Unfractionated Heparin. Heparin is a fast-acting blood thinner used to treat heart attacks and pulmonary embolisms.

-

The Therapeutic Window: Heparin is dangerous. Too little, and the clot grows; too much, and the patient bleeds into their brain.

-

The Goal: Doctors aim to keep the APTT at 1.5 to 2.5 times the normal control value (e.g., 60–80 seconds).

-

Why not INR? Patients often ask why they can’t use the INR test (used for Warfarin). The answer is biological: Heparin affects the Intrinsic pathway (measured by APTT), while Warfarin affects the Extrinsic pathway (measured by PT/INR). They are chemically distinct systems.

Conclusion: More Than Just a Number A “high” APTT result is never a diagnosis in itself; it is the start of a detective story. Is it a genetic lack of Factor VIII? Is it a deceptive auto-antibody causing clots? Or is it simply a Vitamin K deficiency? By understanding the specific pathways measured by the APTT, hematologists can prevent catastrophic bleeding events before surgery and ensure that blood-thinning therapies save lives without endangering them.